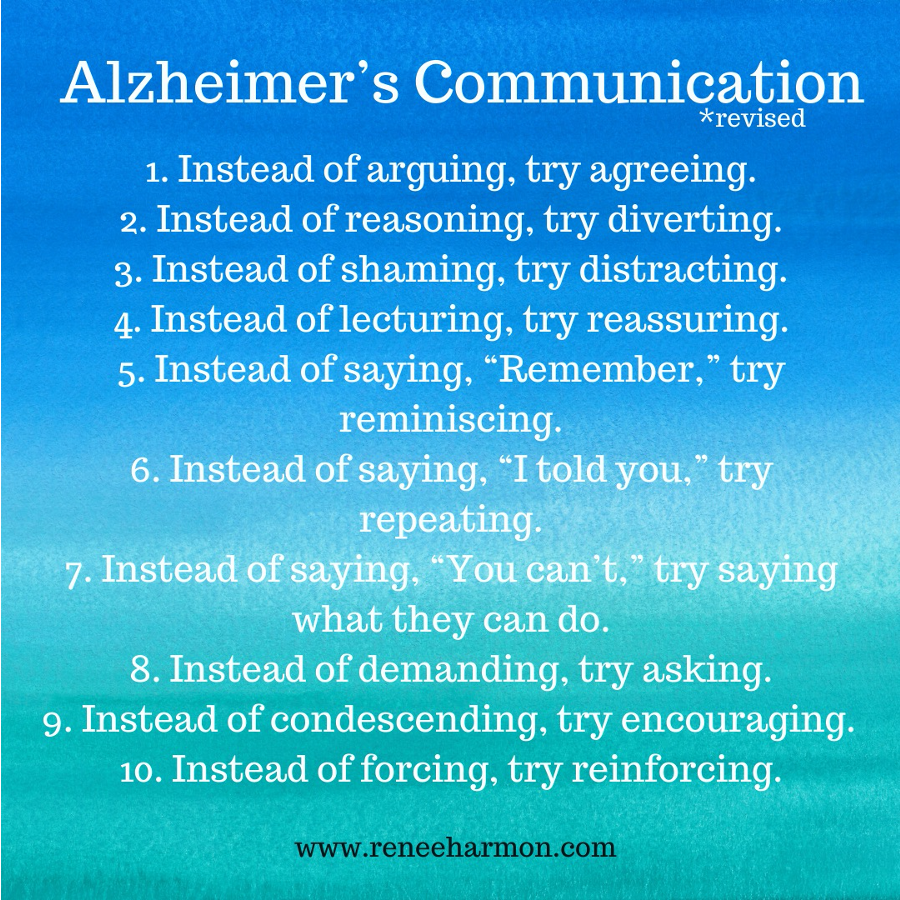

Let’s finish up this list of communication tips. Maybe I can get through them with more honesty and without beating myself up too much!

The eighth suggestion reminds me of struggles with my mother when I was an adolescent. When she would ask me to do something when I was busy doing something I was enjoying, I might answer, “Let me finish this first.” If that wasn’t acceptable to her, she would then tell me to do it right then. As a teenage, this would infuriate me, and I would reply, ” If you want me to do something, just tell me, don’t ask me!” She just could not win. But in general, as adults, don’t we all prefer to be asked to do something rather than demanded to do so? This was the approach Harvey and I had always taken with each other, so it continued after his diagnosis. At some point, though, whenever I asked Harvey to do a task, he would reply, “OK!” but not understand what I had asked and not do it, or he would resist me. I had more success if I used the phrase, “Let’s (insert request) now,” or “It’s time to (insert task),” and maybe lead him by the hand and help get him started.

The ninth suggestion is a reminder that even though our loved ones are operating at a lower cognitive function, they are still human beings of worth and who have feelings. They may not understand your words well, but they can sure pick up on the tone of your voice and any condescension! Condescension can be subtle, too, though, such as speaking to your loved one in “baby talk,” or calling them by belittling names such as “Cutie” or “Sweetie.” They are still adults, and they deserve the respect each individual deserves. Encouraging them in a task is the much better approach.

This last suggestion refers to physical force versus teaching. When your loved one with dementia doesn’t understand what you are asking of him or her, forcing their cooperation will not work. They will not understand why you are violating their bodies and their autonomy by forcefully doing something to them. For example, instead of grabbing the toothbrush from your loved one and trying to brush their teeth for them, it’s better to mimic the movements you want, or even place your hand on top of theirs and do it together. This is reinforcement. I have a horrible memory of trying to forcefully wash Harvey’s hands after a poop incident. It did not go well! It didn’t help that I was screaming at him, ignoring all ten of these suggestions.

And that concludes my dissection of these Ten Commandments for better communication with someone affected by Alzheimer’s disease. Please share your successes and failures in the comments if you’d like. Do you think these suggestions should apply to all adult interactions? How are these suggestions different from suggestions on communicating with children?

Next week, I’ll be discussing some specific communication skills caregivers can employ based on the stage of dementia the loved one is in.

2 Responses

These are wonderful suggestions and thought provoking as well. Hindsight is always better, it is in the moment that it’s so hard. You are such a ray of light and your transparency is appreciated. The rest of us have so much to learn.

Thank you for sharing your heart.

Love you.

Thank you, Leigh!